Why it matters: All that packaging we’ve treated as disposable may finally be reborn. Researchers have cracked the code for turning plastic back into the building blocks to make new plastics. It could revolutionize recycling, which studies have shown is broken.

Researchers at UC Berkeley have developed a new catalytic process that can vaporize the polyethylene (single-use bags) and polypropylene (hard plastics) that dominate trash piles, converting them into propylene and other hydrocarbon gases. Those gases can then be used as feedstocks to manufacture virgin plastics again, enabling a truly circular economy.

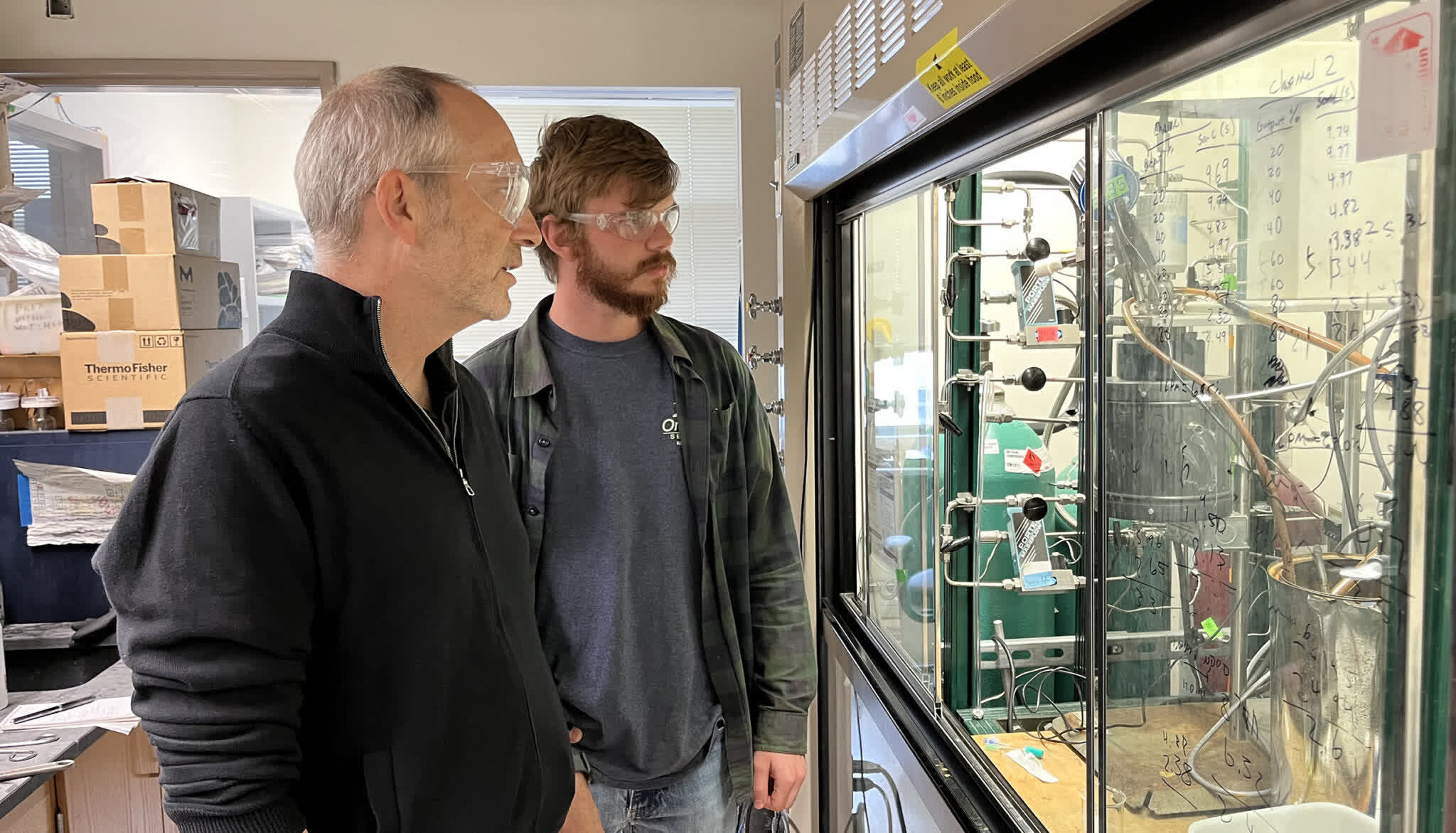

“So much of what’s around us is made of these polyolefins,” said UC Berkeley Professor of Chemistry John Hartwig, who led the study. “What we can now do, in principle, is take those objects and bring them back to the starting monomer by chemical reactions we’ve devised that cleave the typically stable carbon-carbon bonds.”

The breakthrough is a big deal because polyethylene and polypropylene plastics account for almost two-thirds of global plastic waste. Around 80 percent of it ends up incinerated, put into landfills, or littered into the environment as microplastics, which eventually find their way into our bodies.

Many have tried and failed to efficiently recycle these plastic polymers back into their monomer building blocks. But Hartwig’s team has now managed it using cheap, solid catalysts that can run continuously on a large scale.

The researchers use two different catalysts to break down polyethylene and polypropylene plastic waste chemically. The first catalyst cleaves the polymer chains, leaving reactive ends. The second essentially unzips those chains entirely by repeatedly exposing the reactive ends to ethylene gas. The resulting output is propylene and propene molecules. Another byproduct is valuable isobutylene gas. All three are used in the chemical industry to make different plastics.

For instance, propylene is a plastic resin used to make clothing, bottles, furniture, and many other products. Propene is a monomer used in many types of plastic production. Finally, manufacturers use isobutylene gas to produce polymers like butyl rubber and high-octane aviation gasoline.

“We’ve come closer than anyone to give the same kind of circularity to polyethylene and polypropylene that you have for polyesters in water bottles,” Hartwig claims.

While companies are trying to cut down on plastics as part of the recent global green awakening, it’s almost impossible to replace the “miracle material.” A recent UN study indicated that e-waste has grown five times faster than recycling efforts. Furthermore, a Columbia University study found that the current global recycling system is mostly broken. Berkeley’s techniques could be a game changer.

Image credit: Woodley Wonderworks